International Strategy for Higher Education Institutions

International Strategy for Higher Education Institutions

Posted on by Vicky Lewis

This is the last in a series of three blog posts looking at the phenomenon of international education hubs – and the implications for UK higher education. The series is based on a session I delivered at the UK-NARIC 2016 Conference in London on 21 November 2016.

In my previous blog post, I looked at national motivations for (and approaches to) developing international education hubs. In this one, I focus on the opportunities for UK higher education institutions to engage with partners in hub countries in new and interesting ways.

In my previous blog post, I looked at national motivations for (and approaches to) developing international education hubs. In this one, I focus on the opportunities for UK higher education institutions to engage with partners in hub countries in new and interesting ways.

Recent political developments at home (notably the Brexit vote and associated noises around constraining international student enrolments at UK institutions) have sparked grave concern within the UK HE sector.

There is already abundant evidence that the UK is becoming a less attractive destination for international students than it once was. Lacklustre international application figures are reinforced by the results of the 2016 ICEF i-graduate Agent Barometer. Over 1000 recruitment agents from over 100 countries were surveyed in September and October 2016. After four years when the percentage of agents rating the UK as a ‘very attractive’ study destination consistently hovered around 64%, the proportion plummeted this year to 48%.

A continued primary emphasis for UK HEIs on international student recruitment seems unwise. It is surely time to adopt a broader approach to internationalisation, seeing it as a way to ‘enhance academic quality and foster global citizenship’ (EAIE Barometer 2015).

There are pragmatic and more idealistic reasons why it’s time for a change in approach.

At the pragmatic end, in the current climate we can no longer count on rising international student recruitment to the UK so we need to think of alternative ways to ‘be international’.

Our international partners expect more equitable partnerships and we need to respond positively to these expectations.

Our own graduates will be disadvantaged if they are not equipped to work in a global context (which means a greater emphasis on developing opportunities for domestic students that involve international and cross-cultural engagement).

We would all be intellectually poorer if we didn’t embrace knowledge from around the world and expose students to global issues.

And, given recent political developments, there is a growing moral imperative for universities to be beacons of open-mindedness and demonstrate to their communities the benefits of rising above parochialism.

International partnerships have been growing in importance as a strand of UK institutions’ international strategies. However, the traditional North-South ‘education export’ model of partnership is being rejected. Partner institutions are looking for reciprocal relationships – not a ‘one-way traffic’, parent-child model. This is made explicit in some countries’ (e.g. Thailand’s) international strategies (see this HEGlobal piece by Bill Lawton).

When it comes to transnational education, increasingly hybrid operating models exist which do not fall neatly into the standard ‘mode of delivery’ categories. For example, student exchanges are being built into in-country delivered programmes. Distance learning is regularly supported via in-country partnerships. Joint schools are being set up in China as an equitable collaboration between Chinese and UK HEIs.

Opportunities exist (and are starting to be recognised) for a two-way process of genuine internationalisation (not just ‘westernisation’ of ‘host’ country provision); a chance to garner cross-cultural value for all involved.

This all fits quite well with the opportunities offered by international education hubs.

First, they are part of a national strategy, so come with government support and commitment. UK institutions that get involved are working with the grain of their partner country’s national priorities.

Second, they tend to be based on principles of collaboration between partners from different countries. These may not always be bilateral institution-to-institution partnerships. They might be partnerships between a UK institution and a national or regional government; or between a number of institutions (local and foreign) and a particular local industry sector.

Third, because different hubs have different drivers and priorities (and are at different stages of development), there are opportunities for different types of institution (with different strengths) to get involved.

However, it is critically important to build up relationships with governments and other key actors first (sometimes specific foreign institutions are invited to become part of a hub, or there may be a tender process). It’s also critical to remember that getting involved represents a long-term commitment and is not about making a quick buck.

This case study, which is taken from HEGlobal’s recent publication ‘The Scale and Scope of UK TNE’, shows the way a UK university has supported Malaysian national priorities while also meeting its own institutional aims.

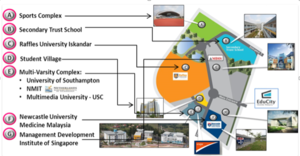

Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia (known as NUMed) was established in 2009, then in 2011, it moved to its current location in EduCity (in the southern state of Johor, near the Singapore border).

Its neighbours in EduCity include University of Southampton Malaysia Campus (which has an engineering specialism), University of Reading Malaysia, the Malaysia branch of British independent school Marlborough College and various other international institutions.

NUMed offers undergraduate degrees in medicine and biomedical sciences, including compulsory clinical experience. It is not a traditional institutional partnership, but operates on what it calls a ‘relationship with Malaysia’ basis to develop strong partnerships with local and national health authorities.

NUMed seeks to ‘meet the needs of both our students and the regional health economy’ and has identified its partnership with Malaysia as a key success factor.

Another factor is the fact that the venture was set up not as an income source but in order to grow reputation and global footprint.

It was always seen as a route for Newcastle into Asia which was designed to respond to local needs in the UK (greater profile and reach within this part of Asia) and to Malaysia’s own local needs (for high-quality medical graduates with locally relevant clinical experience).

NUMed also notes that the experience of having to meet both UK and Malaysian accreditation requirements has heightened programme quality, with the learning from this experience being transferred back to the UK.

There are numerous questions that institutions should ask themselves before embarking on any long-term international venture in a hub country.

Most important is probably the need for alignment between the hub country’s national priorities and your own institution’s aims and areas of strength.

It’s also important to work with what you already have - in terms of experience, contacts and existing partners in countries under consideration.

It is essential to do plenty of research and understand what support is available from the government or other sources and what the expectations are of foreign institutions. Market intelligence gathering can also, in itself, be a form of relationship-building as the process involves engaging with key stakeholders.

Are there any constraints which might rule out viability, such as the hub only looking for world-ranked partners; having high foreign investment expectations; or appearing to restrict academic freedom?

Different hubs have different preferred partnership models. These need to work for your institution as well as for the hub itself. Then come the questions about resource implications and risk management.

Ultimately, working within a hub needs to be a partnership where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

So what guidance is out there to help institutions navigate the hub landscape? I’m going to pick out just two sources of guidance and information. There are many more, including UK-NARIC’s recently launched Global Connect service.

HEGlobal is a joint initiative between UUK International and the British Council. Its aim is ‘to empower UK universities’ TNE activities’. It does this through events, research, facilitating the sharing of experience, and signposting to advisory and international business development bodies.

The HEGlobal website is full of useful resources, including an excellent page on further information sources. Their recent publication on ‘The Scale and Scope of UK TNE’ provides a useful overview of who is doing what where (and some good case studies).

Earlier this year, the British Council launched its (publicly available) Global Gauge. This measures (for 26 countries) different aspects of the enabling environment for international higher education provided by national governments. The country notes sections are particularly useful.

Three areas are scrutinised: openness; quality assurance and recognition; access and sustainability. The only down side is that some hub countries are not included (though a project is underway to extend the number of countries covered). The database is easy to manipulate, meaning that particularly influential factors can be isolated.

Over this series of three blog posts, I’ve tried to show that, while international education hubs contribute to heightened global competition for international students, they also offer a range of opportunities for international collaboration. Given the need for UK universities to find new ways to ‘be international’, it is worth exploring partnership development in hub locations. One critical success factor is establishing compatible goals (on a number of levels) and recognising what each partner brings to the table.

At a time when changes in the global education landscape and political developments at home are putting pressure on UK HEIs, it seems timely to explore opportunities to collaborate across cultures in a process of mutual internationalisation.

|

|